By Jacques Voorhees Length: 8,200 words. Date: August 23, 2017

I’d seen a solar eclipse before, and been underwhelmed. It was 1998, while touring an emerald mine in Colombia. After three hours below ground, we’d returned to the surface in time to see—not much. Our eyes were so adjusted to the dark that even when the sun’s light faded it still seemed pretty bright. Someone had a pair of those tiny eclipse glasses, which we shared, and—yeah—you could see the black disk of the moon partially cutting into the sun. Seeing a bright round orb in the sky being “eclipsed” by another object and thus becoming a crescent shape isn’t exactly a new phenomenon. We see it every night as the moon goes through its stages.

Anyway, after that earlier experience, when I heard another was going to hit the United States on 8/21/17, I wasn’t excited. News reports were making a big deal of it though. Apparently the eclipse would be “full” in some areas, meaning 100% of the sun’s disk would be blocked. OK, fine. That would be just like a new moon, right?

By the way, this isn’t a joke. Earlier in the week a mom was calling-in to a talk show where a famous astronomer was the guest of the day. “Can you please explain to my ten-year old how it’s possible for the moon to block the sun, when the moon isn’t full?” she asked.

Yeah, that one’s a real head scratcher, isn’t it?

Anyway, although the eclipse was no big deal to me, apparently it was a big deal to everyone else, judging by the coverage. Maps showing the path of the full eclipse as it crossed the United States began appearing everywhere. Keystone, Colorado was well outside the path, although even here a 98% eclipse was forecast, which is darn close to 100, seemed to me. Not that I cared. Yet many people did, as reporters weighed in on the mass migration forecast from the Denver area, north on I-25, into Wyoming and Nebraska. It seemed eclipse seekers had booked up all the hotels along full-eclipse path, and serious traffic congestion was expected.

I could not have cared less.

There’d been a run on eclipse glasses, and finding a pair now was akin to trying to buy the latest X-Box video game on Christmas eve. I hadn’t yet heard of fights breaking out in parking lots but apparently eclipse glasses were not obtainable.

No matter. I’d be watching on TV—if at all.

Far more interesting was Kristen coming to visit for the weekend. This was still a new phenomenon. Our daughter had been living on the East Coast for over a decade and, between college, law school, and working as an attorney in Manhattan, we’d be lucky to see her even a few times a year. But a few months ago, having landed her dream job as a corporate counsel for DigitalGlobe, Inc. in Denver, the leading satellite-earth-mapping compay, Kristen could now drive up for the weekend anytime she wished.

On Saturday morning, as was becoming tradition, we drank coffee and planned the weekend’s activities: perhaps an early morning bicycle ride, afternoon sailing on the lake, maybe a mountain hike, dinner somewhere…stuff like that.

“So, is anyone interested in driving up to Wyoming to see the full eclipse?” Kristen asked.

“I’ve been watching the news,” said Derry. “It’s going to be a zoo up there.”

“I saw an eclipse once,” I noted. “It was pretty boring.”

“You saw a full eclipse?” Kristen asked.

“No, partial.”

“That doesn’t count.”

“Are you interested in actually going there?” asked Derry.

“I am going.”

We shouldn’t have been surprised. Kristen is the hard-science member of the family. With a degree in biochemistry, a minor in physics, a founding member of Middlebury College’s Astronomy Club, and now working for a space-sciences company, of course she’d want to see the eclipse.

“It might be hard to find glasses,” said Derry, not being negative but appropriately concerned for her daughter.

“I have glasses. DigitalGlobe bought glasses for all its employees.”

“The traffic out of Denver might be a problem if you go that way. They’re predicting I-25 north will be a parking lot.”

“I’m not driving from Denver. I’m driving from here. I’m going straight north into Wyoming, through Walden. You know, back roads.”

“Those are pretty deserted highways. You shouldn’t go alone. One of us at least should go with you.”

“Who wants to come with me?” she asked, excited at the thought of company.

“Well, no one can go with you if we can’t buy another pair of eclipse glasses,” I noted. “Let’s call around and see if we can find any. If we can’t, that will help make the decision.”

Derry made some phone calls to local optometrists and others, but reported back that none were to be found. Anywhere.

“I can share the pair I have,” Kristen offered, which didn’t sound too encouraging. It was a long drive (over five hours), and if only one person could see the eclipse at a time… Hmmm.

“How about hotels,” asked Derry. “Is it too late to get a reservation?”

“I don’t need a hotel. I can leave super early, like 1 am, on Monday morning. Or leave Sunday afternoon, and camp somewhere on the way. I could sleep in the car.”

A few weeks earlier Kristen, now gainfully employed, had purchased a brand new Jeep Cherokee “Trail Hawk,” and was eager for a road trip—preferably one where she could fold down the back seat and try sleeping in her car.

In the end, I volunteered to go. I didn’t care about the stupid eclipse. But a drive north through Walden and into Wyoming piqued my interest. This was an area I’d never visited, and I hadn’t been to Wyoming itself in over thirty years. I’d bring a tent and sleeping bag, so we could camp if needed. Or maybe find some out-of-the-way motel. Derry endorsed this plan, as she liked the idea of the two of us making the trip together.

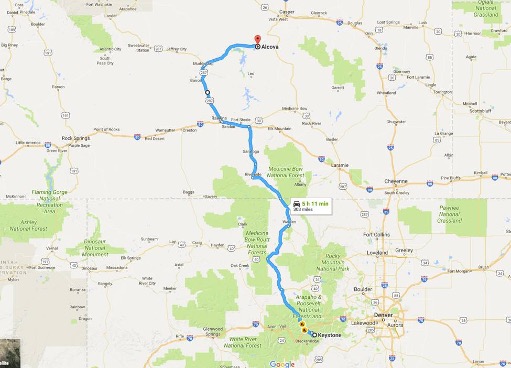

Keystone to Alcova: 5h 11min–on a good day

We left the county Sunday at 3pm, driving north on Colorado Highway 9. The first part, to Rabbit Ear’s Pass, was familiar territory. But this time instead of dropping down into Steamboat Springs, we veered right into what’s known as North Park—another area I’d never been to. Colorado’s North Park is as majestic as its South Park cousin (which gave its name to the famous TV show). These aren’t parks in the normal sense, but rather large flat basins between mountain ranges. Kristen, who’d been studying up on the area, explained that Native-Americans had loved North Park because the buffalo were confined by the mountains and just wandered around in a small area, making hunting so much easier. That did sound better than chasing them all over Nebraska.

Earlier that day we’d plotted the band of total eclipse on a highway map of Wyoming. There were two components to plot: the path of the eclipse and the path of the hordes coming up from Denver like locusts, spreading into Eclipse Country. We needed to be well into the first, and as far from the second as possible—with the least driving needed to reach such a place. With these parameters, we’d chosen the town of Alcova—just east of Casper—as our final destination. It was sufficiently away from the I-25 corridor, and fully in the path of the “totality.”

Eclipse Country

We crossed into Wyoming as clouds swept in from the west, and found ourselves in ranch country. Cowboy country. In fact, here was a cowboy now, riding a black horse and herding some renegade cattle into a corral—just like in a John Wayne movie. Wyoming is so sparsely populated that despite being one of the country’s largest states, it only has three electoral votes. Tiny New Jersey, by contrast, has fourteen.

At the Colorado/Wyoming border

Wyoming is mostly open range. That’s not a romantic, wistful description. Open Range is a thing. When you drive cross country, the highway is normally bordered by fences, typically barbed wire. This keeps the grazing livestock and other animals off the roads. But Open Range is truly open, and there are no fences. So the highway department has to label it with formal Open Range signs—meaning: watch out for animals. They could be anywhere. And often were.

As we made our way north through broad valleys, and vast plains, herds of deer, cattle, or sometimes even antelope were everywhere. But there was plenty of grass to go around and the mammals wisely kept away from the highway itself.

The late afternoon sun shone through rain clouds, as light bounced off the mountain peaks—low ones by Colorado standards. But the operative word was: late, and we needed to make a decision. The only significant town we’d pass through on our route was Rawlins, WY, population 9,259, about two hours shy of our ultimate destination. Rawlins is an exit off Interstate 80, and if there were motels anywhere—even if all booked up—they’d be here. But if we couldn’t find a room, we’d have to camp, and finding a spot would be tricky after the sun went down.

We joined Interstate 80 and were a few miles east of Rawlins when we passed a giant oil refinery, seeming as out of place here in Ranch Country as a herd of cattle would be in New Jersey. Most gas stations in Wyoming are the Sinclair brand, and sport the green-dinosaur Sinclair logo. The exit by this refinery said “Sinclair.” A small housing community had grown up here, and apparently the whole thing was named Sinclair. It was a company town, an oil town, plunked down in the middle of the open range. If this was the land where the deer and the antelope played, the giant Sinclair refinery was a mean adult, snarling: Play somewhere else, dammit, we’re working here.

Highway signs began listing the motels in Rawlins, conveniently grouped around a single exit apparently. Wyoming’s cell coverage is awful. Three bars, said our phones, but they were weak bars, and insufficient to pull up a website like Expedia. We’d have to check the old fashioned way, by stopping at each hotel and asking if they had vacancy. We’d been driving for hours already, and a real bed and nice dinner sounded so much better than a sleeping pad on the rocky ground, and trying to cook freeze-dried food over a backpacking stove in the dark. There’d be enough “dark” tomorrow.

We pulled into the first hotel’s parking lot.

“World’s stupidest question,” I said to the friendly hotel clerk. “Do you have any vacancy?”

“We’re all booked up, I’m sorry,” she said. At least she hadn’t added: “Are you friggin’ kidding me?”

“Is everyone else booked up, too?”

“Totally,” she said, sympathetically, and I mentally prepared for a tough night on the ground, somewhere off the shoulder of Highway 287.

“But would you like me to call around, and just check?” she added.

“Oh, that would be so kind of you!” A faint hope, but it was the only kind we had.

She called one number, then another, then a third.

“Oh really?” She turned to me. “They have one room left.”

“Grab it!”

She handed me the phone, and I gave my name, then my phone number.

“And are you still at 35 Snowberry Way, in Keystone?” asked the voice on the other end.

What the hell? Some tiny motel in Wyoming knew where I lived? How creepy was that? But I calmed down when she explained it was the Comfort Inn, I was a member of their frequent guest program, and my phone number had pulled up the record. Soon we were pulling up to the entrance, and as I walked over to the busy reception desk I announced: “Hi, we just made a reservation about two minutes ago…”

His name was Carlos, and he acted like my best friend: “Oh, I am so excited for you! Do you realize how lucky you were to get that room?”

“Pretty lucky?”

We’ve been booked solid for six months. Same with every hotel in Rawlins. We just got a cancellation a few minutes ago. You grabbed the room only seconds later.”

We became instant celebrities. Carlos announced to the other desk clerks that we were the ones who’d scored the room at the last minute. Apparently Kristen and I had won the Rawlins Hotel Eclipse-Day lottery. Everyone was both astonished, and thrilled. I half expected a TV crew to show up to film the event. We were indeed celebrities, at least at the Comfort Inn reception area.

We felt less fortunate when—while filling out the paperwork—we discovered the rate: $300. I’d never paid more than $85 at a Comfort Inn in my life. But, OK, if we split the cost, it wasn’t the end of the world. And suddenly even $300 seemed reasonable, as others came in, seeking rooms, and we overheard the conversations.

“Travelodge has two rooms left, but they’re $700 each.”

“Holiday Inn Express is charging $900 for a bed.”

Astonished travelers erupted in predictable outrage, and there were angry murmurs of “highway robbery,” “illegal price gouging,” and the like. Those blessed folk who’d had the foresight to book months earlier were now arriving, while cursed and tormented souls left the reception desk and walked back out the door, heads shaking. I wondered if we should rent them our camping equipment for $250 per sleeping bag, with freeze dried food thrown in for free, but they’d probably call that price gouging as well. And we still had our own gauntlet to run: where could we find dinner, in a town packed to the gills with eclipse seekers?

The hotel manager was a woman of advanced-middle-age, with graying hair, a homely face, and the look of a hard life about her. But her warm smile eclipsed (sorry, I couldn’t resist) everything. We asked if there were restaurants nearby.

“You might want to eat right here, at the hotel,” said friendly and helpful Sherry.

“Oh, you have a restaurant that’s attached?” I’d never known a Comfort Inn to have a restaurant, other than the free breakfast nook.

“Oh, yes, you can eat here,” she said. “We have the best chili in Wyoming. Everywhere else in town is packed. One couple tried to make a reservation for dinner and the earliest they could seat them was 9:30.”

We needed to be asleep by 9:30, in anticipation of an early start to reach Eclipse Ground Zero.

“Chili sounds great!” I said. “Where is the dining room, exactly?”

We were ready to eat immediately.

“Just around that corner,” she said. “It’s where we serve the free breakfast in the morning.”

“Oh, you mean there’s no restaurant per se?” I was getting confused.

“No. But we realized it was going to be a problem for our guests arriving tonight with all the restaurants full. So we decided to cook up a huge pot of chili. It’s my mom’s original chili recipe. Like I said, it’s the best in Wyoming.”

“So you mean…it’s free?”

“Yep. All you can eat. We have grated cheese, fresh cornbread muffins and saltine crackers too!”

Better and better. We’d won the Rawlins hotel lottery, and now were being offered Wyoming’s best chili for free. Plus muffins.

“Oh, and let me give you the gift bag,” said oh-so-friendly Sherry.

She handed over one of several dozen brown bags behind the reception desk. Inside was an apple, an orange, and…and…two pairs of eclipse glasses!

“You’re giving out eclipse glasses for free, as well?” asked Kristen.

“Yes, of course. Everyone needs eclipse glasses to see the eclipse,” she admonished, as if we might be unclear on the subject. “So we ordered these months ago, for our guests.”

Three hundred a night was beginning to look cheap.

“Wait, before you leave, you need to put one of these on your car’s windshield. We made them up special, just for the eclipse. You can keep it as a souvenir!”

She handed us a vinyl-coated parking pass, with colored drawings of the phases of an eclipse, and the words: Total Solar Eclipse, August 21, 2017, Specialty Parking Pass.

A parking pass, neatly converted into a souvenir.

Who does that? For that matter, who makes free chili (let alone the best in the state) and gives it out to guests who might have a hard time finding dinner reservations? Who gives out free eclipse glasses, when there were none to be had west of the Mississippi?

We consumed three bowls of chili each, yes it was that good, and the little cardboard bowls somehow made it more special, not less. While we were devouring muffins and crackers, another friendly staff member came out, this one wearing an apron, asked if we were enjoying our chili (we were) and began castigating herself for having let the grated cheddar cheese run out. She scurried away amidst apologies, promising more cheese in just an instant.

And did I mention the warm chocolate chip cookies at the front desk?

I reminisced on every great hotel I’d stayed at. Let’s see, there was the Grosvenor House in London, the Emirates Tower Hotel in Dubai, the Peninsula in Hong Kong. Marriot Marquise in New York. Mark Hopkins in San Francisco. Five stars all. Yet none could compare in customer service to the modest Comfort Inn of Rawlins, Wyoming.

The review I’d be writing for TripAdvisor.com was going to melt the Internet.

Here was something interesting. In the lobby a pair of elderly ladies, giggling like school girls, were making hats out of aluminum foil, and using scotch tape to attach antennas.

They both wore eclipse-themed t-shirts.

“What are those helmets for,” I asked, curious. “Are they to protect you from the eclipse?”

“They’re to protect us from anything!” said the ladies, giggling again. I took their picture, with the foil hats, while others standing in the lobby applauded.

Eclipse-fever was in full swing.

Full eclipse protection

And that was a problem. Even this far west, away from the Interstate 25 corridor, hordes of eclipse seekers were everywhere. The nominal two hour drive up Highway 287 to Alcova could be bumper to bumper in the morning. I imagined an endless and stationery stream of RV’s, motorhomes, trailers and tourists in all manner of vehicles, bringing traffic to a standstill.

To hell with that. We’d leave early and beat them all. Real early. Like five a.m. We needed to be there by 11. Six hours for what should be a two hour drive, gave us a 3 to 1 margin of error.

“We’re planning on going to Alcova, to see the full eclipse,” I explained to Sherry.

“Alcova’s a great choice,” she agreed.

“We’re going to leave early, to beat the crowds. But how soon do you think people will start heading up there?”

“Well, I can tell you guests are asking for wake up calls like around 2 and 3 am.”

“That early?”

“Yep.”

“So how bad do you think the traffic will be on Highway 287?”

“Bad,” she said. “Can I give you some advice?”

“Sure!”

She turned to Kristen, and smiled.

“Hon, what kind of a car do you have?”

“A Jeep Cherokee, Trail Hawk!” said Kristen, proudly.

“Good girl!” said Sherry the Wyoming local, who clearly approved of rugged four-wheel-drive vehicles.

“OK, then here’s what I suggest.” She pulled out a highway map of the state.

“This is how locals would get there. It’s shorter by distance, but it’s a bad road. A lot of its unpaved, very rugged, cattle guards, switchbacks, and you have to watch for wildlife everywhere. Zero cell signal.”

She grabbed a yellow highlighter and drew a line along a very primitive road connecting Sinclair to Alcova.

“In some places, you won’t be able to drive more than 20 miles per hour.”

“How long would it take?” asked Kristen.

“At least two hours. Three at the most.”

We’d already decided the 287 route would take two hours if no traffic. But if it turned into a parking lot from hell, it might shut down entirely.

Sherry also pointed out another, much longer route, albeit all paved, which circled in from the East. She thought even that would be better than 287.

Back in our room, we agonized over the choices. The unpaved, scary, locals’ road sounded much higher risk. If we got a flat tire, or found some section washed out by a flood or something—or got lost in the dark—we’d certainly miss the eclipse. But if 287 was shut down, we’d also miss the eclipse. The third route looked just way too long.

In the end we chose the local’s road. At least there wouldn’t be any RV’s to pass. And if Kristen’s brand new Jeep Cherokee Trail Hawk couldn’t handle it, nothing could.

We’d been refueling the car almost every time we passed a gas station—hearing warnings of long lines and sparse refueling stops. So when we started off at 4 am, the tank was full.

The route required heading east a few miles on Interstate 80, and exiting in Sinclair for the trip north. Sinclair’s monstrous oil refinery was lit up like Manhattan against the black skies.

“Wow, the oil refinery’s beautiful!” said Kristen.

“OK, that might be the first time ‘oil-refinery’ and ‘beautiful’ have ever been used in the same sentence.”

“I’m easily impressed,” she admitted.

But after leaving Sinclair, all light vanished. It was indescribably dark.

“Is there any moon tonight?” I asked.

“Are you serious?”

“Yeah, why?”

“Dad!”

“What?”

“Of course there’s no moon tonight!”

“Why, of course?”

“Because tomorrow morning, the moon will be eclipsing the sun! That can only happen when it’s a new moon. Meaning, it can’t be out tonight with the sun shining on it, if it’s going to be eclipsing the sun in a few hours. It can’t be in two places at once!”

“Oh. OK. I guess that makes sense.” To Kristen-the-Astronomer, this was obvious. I was still trying to get my head around the orbital mechanics. The moon always confused me.

The trip was as rough as Sherry had warned, but the real hero was the Jeep’s GPS navigation system. It didn’t care we were out of cell range. It was fed by satellites. Without it, we’d have become hopelessly lost. The rough, winding, up-and-down road was cursed with an infinity of intersections, most of which were probably ranch roads or wilderness access routes, none of which were marked. But the GPS knew them, and dutifully guided us through these lost hills.

Except once. It wanted us to go right, but as soon as Kristen turned, she stopped the car.

“This doesn’t feel right,” she said. Picking up her backup GPS, her iPhone navigation app, she nodded. “The iPhone agrees. This isn’t right.” Then she zoomed both of them out, and it was clear both routes merged again some miles ahead. “Oh, I know what’s going on,” she said. “I programmed the car’s GPS to always choose the shortest route. The iPhone was told to choose the best route. That’s why they’re disagreeing. This shorter route may be shorter, but I think it’s going to be a worse road.” She made some changes to the car’s GPS programming, and suddenly it was in agreement with the iPhone.

Before we continued, Kristen shut down the engine and turned off the car’s lights. All of them.

“Look outside,” she said.

It was the blackest night I’d ever experienced. Even crossing the Caribbean Sea on Island Skipper the humidity combined with the starlight created more ambient light. Here, in the dry air and high elevation of Wyoming, lost in unmarked hills hours before sunrise—and did I mention no moon?—the landscape was totally black. You couldn’t see anything ten feet from the car.

But the sky? The sky was alive, and dancing with light. This was how the sky always must have looked before electricity was discovered. This was how the sky looked to caravans crossing the Sahara. To the astronomers of ancient Egypt gazing up at the constellations and naming them. To most everyone before about 1900 when a thing called light pollution destroyed our ability to experience the night sky’s glory.

We opened the sunroof and the Milky Way was revealed, wonderfully clear and sparkling. Kristen began pointing out various constellations, the orange orb of Jupiter, and even the Andromeda galaxy. But I’ve never been interested in constellations. They’re just silly names given to random groups of stars. You could grab any combination of stars and give them a new name. The whole thing was meaningless. But the Milky Way? That’s fascinating. Our galaxy appears as a vast band of light, hundreds of billions of stars making a pathway across the sky. We were in that swarm, ourselves. Our sun—currently hidden behind the Earth—was a member in good standing of a vast, spatial tapestry. Who cared about a once-in-a-lifetime solar eclipse, when the Milky Way was there for us to see almost every night? At least if you’re in uninhabited parts of Wyoming.

There was something else here: silence. Rarely does one escape all sound. Even in the wilderness at night, camping, there’s wind blowing through the trees. Noises from small animals. Maybe overhead, a jet flying. Thunder somewhere in the distance.

Here, there was nothing. No wind. No trees. No airplanes. Nothing. Utter silence. I’d experienced this only once before: in an isolated cabin in Northern Finland, above the Arctic Circle, in the depths of winter. Here was that same intense level of quiet.

But a magnificent sky and infinite silence weren’t the phenomenon we’d come here to appreciate. Kristen pulled back on the road and—with the GPS’s now in agreement—continued our journey in the dark.

Perhaps over on Highway 287, RV’s and trailers and semis were bringing traffic to a crawl. But on this road the problem was antelope and deer. We passed only one car, heading south, but saw perhaps two hundred highway mammals. It was serious enough we had to divide up the workload. Kristen was better spotting the deer on the side of the road, or darting across it. I was better with the road itself, and the major holes, cattle guards, and other obstacles.

So I’d frequently yell “bump!” while she’d frequently yell “deer!” before hitting the brakes for one or the other. Often half a dozen deer or antelope would run across the road, mere yards in front of us. Between the bumps and the animals, we frequently could not drive faster than 20 miles per hours—sometimes less—as Sherry had warned. Once, we came across two large deer with majestic antlers—the kind you see on the cover of Outdoor Life magazine, with a self-satisfied hunter holding a high-powered rifle, posing beside a dead one.

But these beautiful animals had nothing to fear from us. OK, I did have a gun. My .38 Special revolver was buried in my pack somewhere. No way was I going to camp in Wyoming—a state filled with grizzly bears—without protection. For gun nuts who might sneer at the thought of trying to stop a grizzly with a .38 caliber handgun, I’ve actually studied up on this. Common wisdom says you pretty much can’t stop a grizzly with any weapon, even the most powerful hunting rifle, if the bear’s charging at you. Even if you shoot it in the heart, it will live for at least two minutes, and needs only thirty seconds to kill you.

But among arm-chair enthusiasts like me, and the experienced hunters and survival experts who actually know what they’re talking about, there is agreement on one thing. Shoot a grizzly in the brain and it will die instantly. Not that that’s so easy to do, of course. But even with the right aim, you still need the right bullet to penetrate a grizzly’s skull. A .38 Special will suffice, but only if you use ammunition packed with extra gunpowder (“plus-p”), and flat-nosed, hard-cast bullets designed for penetration. They do make such things. And after Kristen and her friend Sandra—camping in Alaska—had experienced a very dangerous encounter with a mama Grizzly and two cubs, I’d bought fifty rounds of it.

Now the gun and its grizzly-capable bullets were buried in my backpack—not having been greatly needed at the Rawlins’ Comfort Inn. I doubted they would be much help during the eclipse, either. But on this deserted wilderness road through the Wyoming darkness, I was glad I was armed. Although if a grizzly did attack, I’d have to ask him to wait a sec while I scrounged in the back and found both gun and bullets because in truth I had no idea where I’d packed either. When it comes to wilderness survival, I’m not exactly Bear Grylls.

At one point in our journey the road pitched downwards so steeply Kristen had to use her “super low” four-wheel-drive gear. We lost so much altitude I had to clear my ears—three times. No way could those RV’s have handled this.

Look closely to see the antelope

We were almost to Alcova when the sun finally appeared (for now), and were sleepy, sore from the constant jostling of the rough trail, and ready for breakfast. Alcova is tiny and we weren’t sure they’d have gas stations, or even the simplest of restaurants. It didn’t matter too much. We had bagels, beef jerky, gallons of water, not to mention that apple and orange included with the hotel’s gift bag. We weren’t going to starve. But restrooms would be nice.

At least we’d arrived inside the total-eclipse band. Now we merely had to find a place to watch the event itself—preferably somewhere high up and with a broad view of the sky. At the intersection with the main highway coming up from Rawlins, we found a General Store and Gas Station. At 7am, we were the only customers.

Gasoline—check. Restrooms—check. When these needs had been met, we wandered into the General Store itself, and found two women running the place, way friendlier than they should have been at this hour.

“Oh, good morning!” said one. “Welcome to Alcova!”

“Are you here to see the eclipse?” asked the other, breathlessly. “Isn’t this all just so exciting? You are going to have such a great time!”

It was beginning to seem likely. But after the beautiful scenery from yesterday’s drive through Colorado and Southern Wyoming, the almost magical good fortune at the Comfort Inn, the glorious night sky in the wilderness, the hundreds of antelope and deer, and now these friendly general-store clerks—well, a mere eclipse might be anti-climactic.

Would you like breakfast?” offered one of the women. “We have the most amazing egg burritos.”

OK, so we wouldn’t have to gnaw on jerky, washed down with dry bagels and water from a gallon jug. We grabbed some egg burritos, almost too hot to eat, and enjoyed them at a little pocket-park behind the general store, guarded over by a six foot tall green dinosaur statue. Did I mention this was a Sinclair gas station?

After breakfast we went back inside and discovered a small room filled with souvenirs and t-shirts. Yes, they even had t-shirts custom made for the eclipse. We bought two and put them on, helping us get fully into eclipse mode.

“So, how’s the weather looking?” I asked one of the women.

“Clear. Totally clear today. Well, except there can always be the stray cloud that shows up, and then quickly blows away. I mean, after all, this is Alcova!”

Apparently Alcova was world-famous for small clouds showing up, and then quickly blowing away.

“Yes, that’s true,” I agreed. “This is Alcova!”

So you really think we’re going to be able to see the eclipse?”

I felt we’d overcome so many hurdles to get here, the event itself seemed unlikely to ever actually happen.

“Oh, you’ll definitely see the eclipse! It’s going to be amazing. You’re going to have such a wonderful time.”

Alongside the counter was a refrigerated case containing a dozen bins of ice cream, like at a Baskin-Robbins.

“So, is this special eclipse ice-cream?” I asked, caught up in the moment.

“It is!” she confirmed. “This is our special eclipse ice-cream!”

It was hard to believe that a full eclipse of the sun was actually a once in a lifetime event in Alcova. These local tourism boosters acted like experts on the subject; as if helping tourists enjoy the eclipse was what they did every day, and had been doing for years.

“Do you need any eclipse glasses?” they offered. “We have a few pairs left.”

We were awash in eclipse glasses by now, and the parking lot was filling up. RV’s, motorcycles, and pickup campers—the hordes we’d feared earlier—were beginning to swarm everywhere. It was time to leave and stake out a good eclipse-watching spot.

Alcova is surrounded by the Granite Hills, and is just north of its namesake reservoir, a popular destination for boaters and water-skiers. Our goal was to be up high, with a clear view of everything, and away from the RV crowd.

We followed a rugged jeep trail up a valley just to see where it went. Yes, we could park here, leave the car, and hike thirty minutes to the top of a high ridge, which no doubt commanded a view to the South and East. But we’d be a long way from the car.

Back on the main highway, we drove southwest and found a paved road which went around the lake. As we climbed high above the water the perfect spot appeared. A small pull-off provided a spectacular view over the lake. After hiking up some nearby cliffs we found the view even better—almost 360 degrees. This was it: the platonic ideal of an eclipse-watching location.

The Granite Hills and Alcova Reservoir

Two hours to eclipse time. The sun was rising higher and it would soon be ferociously hot, here on the exposed rock. We grabbed necessary supplies from the car: the jerky, the snacks, four liters of water, foam pads, the tent (to provide shade) and most important of all: the eclipse glasses.

Preparing for the eclipse

The best eclipse-watching spot in Wyoming

By the time everything was set up properly it was time to start worrying about clouds. Remember, this was Alcova. There was a small line of them to the northwest. Pretty far away.

If this hadn’t been Alcova, I’d not have worried much. But with nothing else to worry about, I stressed out over the clouds. Possibly they were moving closer. Hmmm.

Kristen was taking a nap in the shade of the tent. I read my book, nibbled on snacks—it’s important to keep one’s strength up during an eclipse—and gazed apprehensively at those clouds.

The morning’s festivities would start at 10:18. Not 10:20. Not 10:15. But precisely 10:18. Kristen even found a website that provided the time to the second. That’s when the moon was scheduled to begin crossing the sun’s disk.

By the way, how do they know these things? How is it possible for humans to be smart enough to predict, to the minute—to the second—when the eclipse would first become visible in Alcova, Wyoming? Whatever else is wrong with the world, you gotta hand it to the astronomers.

I had just enough cell signal to be able to check Facebook messages, and here was one that concerned me. A friend in New Jersey was warning that the cheap eclipse glasses might not be that reliable. “I wouldn’t trust my vision to a ten cent strip of plastic,” he wrote. Hmmm.

When Kristen woke up we discussed the issue, and decided to take the warning seriously. We’d neither of us stare at the sun for long periods. Just briefly, a few seconds at a time.

The clouds were definitely getting closer. A race was on, between the eclipse and the clouds.

In the meantime it was getting hotter, and the shade was mostly gone.

“I’m boiling,” said Kristen.

“You won’t be for long. Remember what’s about to happen.”

“You think that will actually cool things off?”

“The sun disappearing? Yeah, pretty sure that will cool things off. That’s why I brought a coat.”

“Hmmm, that hadn’t occurred to me. I think I have a sweater in the pack, but it’s hard to imagine needing it.”

“Better find it now, while there’s still some light,” I suggested.

Fifteen minutes before eclipse time, beginning to get nervous, I recited for Kristen the plot synopsis for “Prisoners of the Sun,” that Tintin adventure in which a total solar eclipse in Peru features prominently. It was the only eclipse story I knew, and it helped pass the minutes to count-down.

Finally it was time. 10:18. Things were starting. We waited a few minutes and then donned the glasses for a quick peek. Yep! A black circular object was cutting off part of the sun. It had started. The astronomers had been right. And they obviously knew Alcova.

I looked around. No change. The sun was as bright as ever. The minutes passed. Nothing was happening. Well, it was more than an hour before the “totality,” as it’s called. Certainly we’d start noticing changes soon. But the only real change was the clouds. They were getting closer. If they arrived during the two minutes of “totality,” the eclipse would be ruined.

Kristen entertained herself by making tiny holes in things, so as to cast an eclipse shadow on the rocks. I backed her up with my camera, snapping a picture whenever something close to a crescent shape appeared. She was even able to do it with her hand, clinching it in just the right way to let a smidgen of sunlight through. I learned the trick as well, and pretty soon we had little eclipse crescents dancing all over the ground. Occasionally we’d look through the glasses and notice the black orb getting bigger and the sun getting smaller.

Making eclipse crescents by hand.

It was much as I remembered from Colombia. The black orb got bigger, the sun smaller, but the overall visible effect in terms of darkness was minimal.

Thirty minutes from totality, and the feeling of the light had changed. It was as if high cirrus clouds were partially blocking the sun. Nothing more than that. Meanwhile the real clouds were still threatening.

Several minutes later Kristen put on her sweater. It was getting cooler, and a wind had picked up—probably related to the eclipse.

The percentage of eclipse had now become huge. Most of the sun was being blocked—perhaps 90%, judging by the size of the crescent remaining. Astonishingly, it was still mostly bright sunlight, here on Earth. Well, not exactly bright sunlight. But if you didn’t know an eclipse was happening, you’d never guess anything was amiss.

Ten minutes to full totality. The clouds were going to lose this race. No way could they move across the sky fast enough to block the sun in only ten minutes, Alcova or not. Our weather had been perfect.

Five minutes to complete eclipse. Looking through our glasses, only the tiniest of crescents remained, and even that was beginning to collapse in on itself, becoming shorter.

But, dammit, it was still mostly regular sunlight. Perhaps equivalent to a cloudy day. The temperature had dropped significantly, but the lighting had scarcely changed at all.

And then it started. Really started. It was as if someone had grabbed the variable-light control in my dining room, and swiftly cranked it down. I could see the light vanish. We went from near normal daylight, to deep twilight, in about thirty seconds. The speed that it happened was astonishing. An hour and twenty minutes from when the eclipse began, and 99% of the darkness happened—all at once.

Darkness descends over the lake

Now we were in full totality. Stars hadn’t come out—quite, but that was only because so much of Wyoming was outside the full eclipse, and was reflecting light back into the atmosphere. I put on my glasses and looked up at the sun. It was gone. I could see nothing through my glasses but blackness.

“Oh my God,” exclaimed Kristen. “I looked up at the sun without the glasses. You can see it. You can see the corona.”

“Is that safe?” I asked.

“Yes, it’s the only time you can ever look directly at the sun, in full eclipse. Look at it!”

I did—and was changed forever.

I didn’t stare long, less than a second. And I didn’t look back at it. I didn’t need to. What I’d seen would be forever burned into my brain—into my soul.

After looking through many pictures of the corona online, this is the one that most closely replicates what we saw. Although ours was scarier.

It was the Eye of Sauron. No, it was more than that. It was the scariest, most fantastic thing I’d ever seen in my life. It was a huge wheel of fire, with a black center, hanging in the sky. A moving, radiating, pulsating, completely in motion, hollow disk of fire. I’d assumed the “corona,” the illuminated radiation streaming off the surface of the sun from behind the moon, would be faint, vaporous, and dispersed. No, this was the intense fire of hell, the mind of God, the elemental power of the universe, on display—naked to the world. Terrifying and spectacular all at the same time. Humbling and inspiring. Majestic and awful. The yin and yang of the galaxy. Good and evil somehow combined and harnessing the power of both.

I didn’t want to look at it again. I’d seen too much already. It was something I could never un-see. Something no mortal should be exposed to. Something that might well give me nightmares—almost certainly would. Something that would exhilarate me and lift me up as nothing else ever could. Something that made clear, in a fraction of a second, how powerful the universe is, how indescribably petty were human beings and their silly concerns.

I thought about the last week and the media’s outrage over how Trump had commented on the Nazis in Charlottesville. None of it was important. Nothing that happened on Earth was important. The Earth itself was not important. Or at least didn’t seem so at the moment, having just gazed into the soul of creation—or whatever that damned thing was up there in the black sky.

I looked at Kristen, or what little I could see of her in the darkness.

“Did you see it?” she demanded.

“It’s the Eye of Sauron,” I said, not trusting myself to say more.

“Yes, it’s absolutely the Eye of Sauron! That’s the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen.”

She looked up at a few more times, but I didn’t. I was too humbled. One such glimpse was enough, for anyone, per lifetime.

And then it was over. Even faster than it had become dark, the light began. It happened so fast you could see it move across the surface of the lake. The western side was bright sunshine, while the eastern half was still in darkness. Then both halves were in the light, and the hills on the far side were dark. Then the hills began glowing again, as a sliver of the sun hit them.

I began to realize what was going on. Even a tiny piece of the sun provides enough light to make it seem like full daylight, or just about. This is why everyone says there’s all the difference in the world between a 98% eclipse and a full eclipse. Of course! A 98% eclipse is hardly noticeable. Even 99%. That’s about when Kristen put her sweater on. You had to completely turn off the sun before everything went dark. Probably even 99.9% wouldn’t have done it.

That makes sense in a way. Imagine a closed room, no windows, no lights, completely dark. Now turn on one light. It’s light! You can see the room, read a book, anything. Now bring in high wattage floodlights. OK, it’s brighter. But it doesn’t change anything that much. You can still read a book, see everything in the room. And so forth.

In fact, duh. The eye itself compensates for different lighting conditions as the iris expands and contracts—ensuring we always have just the right amount of light. But the iris can only open so far, and beyond that we experience true darkness. That’s why a full eclipse is a big deal, and anything less, isn’t

Well, yes, plus with a full eclipse, you get to stare into the soul of the infinite, and have your spirit forged anew in the crucible of eternity. That part’s a bonus. Or the ultimate price, take your pick. I was still trying to figure it out, and recover spiritually. I’d been touched by the divine, or forever haunted by the profane, or fused with the power of the two together.

Sure, on an intellectual level, I knew my reaction was silly. I’d merely been overwhelmed by my first and probably only-ever view of the sun’s corona, live, in the wild. It wasn’t a NASA photograph. It wasn’t some CGI Hollywood phantasm. It was real. I’d seen it. But it had changed me. Probably no super powers had been bestowed, or at least no important ones. But I would never feel the same way about the sun, that’s for sure. I finally knew what it really looked like. Yikes!

During the full eclipse, I’d heard horns honking, people whistling, applauding, and yelling—much like after an NFL touchdown. They were cheering the sun. Or maybe the moon for having eclipsed the sun. Or something. Or maybe each of them had seen that Eye of Sauron, and been affected as I had. They didn’t know whether to laugh, cry, applaud, or crumble into emotional ruins. Again, it was much like an NFL touchdown, depending on who scores.

***

The whole thing was over now and it was time to return home. Or try to, depending on traffic.

We had choices. Follow our dirt road back to Interstate 80, from where we could drop down on secondary highways into Colorado. Return to Rawlins on the “normal” highway and retrace our steps from there. Or head east to Casper, and then brave Interstate 25 down to Denver. With normal traffic, that would be the fastest. But everyone was predicting I-25 would be a parking lot, after the eclipse.

We chose the normal highway to Rawlins, and at first this seemed a good idea. Traffic was heavy, but it was moving fast, like 75 miles per hour—although that’s slow by Wyoming standards. At this rate we’d back in civilization quickly.

Half way there we got distracted by a vast dome of a rock, several hundred feet high, with people climbing on it. A highway rest area had been built, obviously to service this strange geologic formation. Independence Rock, we learned it was called, an important landmark on the Oregon Trail which apparently we were just now crossing. So we stopped, used the restrooms, climbed the rock, read the little placards everywhere explaining the history of the place, and then continued our journey south.

Independence Rock on the Oregon Trail

Climbing to the top

The Eclipse A-Team — With T-shirts

In two miles traffic slowed to a crawl as an intersecting highway coming out of the northwest merged with ours, and on it was an infinity of cars, moving at a snail’s pace. Good grief, would this be our speed, for the 40 miles remaining to the Interstate? But after the merge point we were soon back to 75mph. We lost another twenty minutes to congestion on the outskirts of Rawlings, and then it was over. We left the heavy eclipse traffic behind as we retraced our steps back into Colorado, through Walden, and finally home to Summit County.

Meeting up with Derry for sushi dinner and an eclipse celebration, she was thrilled to hear we’d had such a good time.

“I’m so glad you went, and also glad you stayed away from I-25. On the news they said it was five hours just from the Wyoming border to Denver,” she said, referring to a stretch of highway that would normally take 45 minutes.

Truly, we had guessed correctly and chosen well.

Either that, or the Eye of Sauron, the Soul of the Universe, had stayed with us, and guided us home safely. Perhaps it always would, from now on. Perhaps it didn’t matter either way. Perhaps nothing mattered. Such was the mystical power of the eclipse…

Fortunately, it didn’t affect our appetite. Eclipse watching burns a ton of calories.