Summit County, Colorado — April 22, 2017

I’d been staring at the darn thing most of my life: a narrow band of snow that dropped almost vertically off a spur of the Continental Divide. It hovered over Arapaho Basin Ski Area in Colorado, tormenting me since I first started skiing here at nine years old.

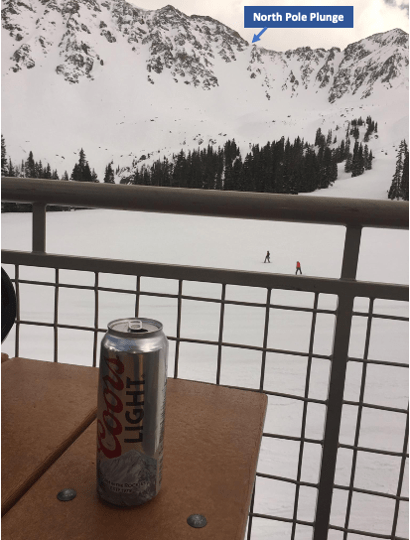

It wasn’t actually a ski run in the normal sense. It’s considered “off piste” or out of bounds, and for good reason. Nonetheless it had a formal name: North Pole Plunge, which pretty much sums it up. But the locals call it something more colloquial: Sh-t For Brains, suggesting the clinical condition of anyone foolish enough to try skiing it.

But the brain cells are the first to go, they say, and enough of mine had departed to consider trying North Pole Plunge after all these years. Why? Certainly not because it sounded fun. It sounded awful. First, you take the Lenawee chairlift to the top of A-Basin which, at 13,050 feet, is the highest-elevation ski area in North America. Translation: no oxygen. From there you start hiking—up. You need to climb Lenawee Peak which is another 500 feet higher. And this isn’t the fun sport-hiking one might do in the summer, with trail-sneakers and shorts. No, here you’re climbing with full ski equipment: skis, boots, poles, and all the clothing and paraphernalia needed to stay warm above treeline.

When you get to the top of Lenawee, the hard part begins. You have to somehow navigate 500 yards across a knife-edge, mountainous ridge, where if you fall it’s a thousand feet down on either side.

If you can make it across the ridge-from-hell, then you’ll finally arrive at the top of North Pole Plunge. And can try to ski it.

A friend of the family, Vicky Wood, is an expert skier by marriage. Her husband Mike, arguably one of the best at the sport in Colorado, married her at age 21, over forty years ago. They’ve been skiing “Double-Black Diamond” runs ever since. It’s about the only thing they ski. Double-Black Diamond means: Extreme Terrain. So I was pretty sure Vicky must have—at least once in her life—skied North Pole Plunge. I asked her about it when I ran into her at the grocery store.

“Jacques, you’re not serious. Don’t even think of trying to ski that. It could get you killed. There is no way I’d go up there.”

“But it’s a life quest. I feel like it’s something I must do, for the good of my soul. An ultimate challenge that has been gnawing on me since I was a child.”

“Find a different challenge.”

“Wait, you’re saying I don’t need to worry about North Pole Plunge? I can let it go? Maybe, like, you’re ordering me?”

“I’m ordering you.”

That had been five years ago, and Vicky’s orders were wearing thin. The trouble was, it wasn’t some distant mountain, hours away. It was a snowfield sort of hanging in the sky, front and center every time I skied A-Basin. Every time I rode the chairlift. Every time I parked in the lot and looked…up.

A year ago our neighbor’s son, Justin Blincoe, skied it and told me it wasn’t that bad. But Justin is sort of a Gaston character, from Beauty and The Beast–excelling at everything; someone who could climb North Pole Plunge from the bottom if he wished. Even so, he offered to take me up the following weekend and, in a moment of weakness, I said yes. Yet when the day arrived we discovered all off-piste skiing was closed. It was too late in the season.

Thank you, Lord. This proves you exist.

Ten months later, the itch was back. Justin was traveling on business too often to be a reliable tour guide, which didn’t bother me at all. More evidence of the deity, and another reason to just say no. But a week ago, April 15, I saw several parties head up the ridge line, and it was obvious where they were going. OK, yeah, they looked like they’d just stepped off the cover of Outside Magazine. Rugged, chiseled features. High-tech gear. Men of steel. In short, my opposites. I watched them start the long hike, and wished I were going with them. Or rather, wished I were brave enough to do so. But I wasn’t, so that was that.

The problem was less the challenge of the skiing, and more a fear of heights. One summer, years ago, I’d climbed up to that ridge-from-hell from the backside, and taken a look over the top. I almost threw up. Total vertigo and a feeling of nausea. It was a sheer drop off. I retreated hastily to gentler slopes.

Now I was thinking of skiing it? Seriously? Well, it wasn’t as crazy as it sounds. If you’re hiking, and slip on what seems a near vertical cliff, you can slide to the bottom, and almost kill yourself. Yeah, I’d done the experiment. But on skis? You’re not going to slide uncontrollably down the hill on skis.

Well, that’s not quite true either. The one and only time my wife had attempted a double-black diamond run, she’d slipped at the top, and slid all the way to the bottom. It was quite in slow-motion, but she just–kept going. I chased her down the hill and got to the bottom before she did, because she wasn’t going very fast. But she was understandably traumatized and stayed that way until the second glass of wine at the lodge took effect. A small keg of brandy might have been better, but where’s a St. Bernard when you need one?

The point is, you’re not going to slide to the bottom unless you fall. If you stay upright, the edge of the skis give you all the control in the world. So, just don’t fall. Simple enough.

Of course, all that was theory. As I watched my betters head up that ridge, I turned away in shame, defeated by my nemesis yet again, and with my soul in torment.

Then I remembered something. I had a daughter. And not just any daughter, but an expert skier, official mountain-guide daughter. She used to lead horseback camping trips into the Collegiate Peaks Wilderness in Southern Colorado. She’d once gone ice-climbing in Alaska, and had backpacked across the Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania last summer. Best of all, she owed me. Six months ago I’d helped Kristen fulfill her own personal life quest: the ascent of Mt. Harvard, third highest in Colorado.

I saw her the next day at a family Easter dinner.

“Kristen, can you come up to Summit County next weekend. I need to ski North Pole Plunge, and you need to help me do it.”

“What’s North Pole Plunge?”

“It’s one of the chutes that comes down off that ridge that overhangs A-Basin. You have to hike up and around it, and then ski back down.”

“Sounds good, Dad. I’m in!”

OK, so things we’re looking better. I’d have my own personal mountain guide, albeit one who’d never heard of North Pole Plunge. I didn’t tell her its other name. Arriving at A-Basin’s parking lot, we took the chair to midway, and then immediately caught the Lenawee lift to the very top. And started hiking.

Given perspectives, it wasn’t possible to see exactly how you get there from here. There was this initial climb, but did you have to go all the way to the top of Lenawee Peak? It seemed more likely you could go part way up and then kind of traverse along the back side to the top of North Pole. Well, we’d see better as we got closer.

We weren’t alone—something I found encouraging. But it was the same kinds of folks from the prior weekend. Young. Healthy. Vibrant. Fearless. I hated them all. But I was glad for the company. Misery loves company.

And after about ten feet of hiking, things were getting pretty miserable. Again, the problem was lack of oxygen. And having to carry all your ski stuff. And climb through snow while you’re doing it.

This is where Kristen really began helping me. Despite her adventurous spirit, she doesn’t run marathons, and gets winded pretty quickly at this elevation. Whenever either of us needed to stop, the other was grateful, which meant we were proceeding up the side of Lenawee Peak at the speed of…two worn out hikers not really in condition for this.

Several times other hikers passed us. We knew this would give them an ego boost, so we were kind of doing them a favor. You know, the way a covered wagon train passing the bleached bones of an ox-team feels grateful that at least they’re still moving. Maybe that would help us on a karma level somewhere ahead.

As if on cue, we reached the first ridge line, and the scenery opened up, paying back karma points. At least we had spectacular views to enjoy while we gasped for breath. It was something.

But there was something else not so rewarding. We now could see the trail fully, and there was no good news here. Yes, we did have to climb to the top of the peak, before we could follow that narrow ridge line across the saddle and over to the top of North Pole. You couldn’t cut across the back side because it was too steep.

After three quarters of an hour we reached the summit and, predictably, my fear of heights kicked in. I’m told animals look away and ignore other animals they don’t particularly like, in a sort of “what I can’t see doesn’t exist’ psychological maneuver. So I tried it along this ridge we were now crossing. I wouldn’t look to the left, because I didn’t like the scary drop-offs plummeting hundreds of feet down. And I didn’t look to the right, because I didn’t like those scary drop offs either, plummeting hundreds of feet down in the other direction. Nope. What I didn’t see, didn’t exist.

Another thing that didn’t exist was a trail. We’d had a trail through the snow on the way up. Now, crossing this saddle-from-hell, this knife-edge, ridge-line, there was no trail. Some of the other climbers were trying to ski it, but that didn’t work out so well. Others were trying to walk along it, while carrying their skis, and that didn’t work out so well either.

What we had to do was put on skis, go a short distance, take off skis, climb a bit over rocks, put on skis, etc. I didn’t like this at all. Skis should be put on and off somewhere flat, like in a parking lot. Performing the maneuver on this narrow rocky cliff was wrong on so many levels. And most of the levels were beneath us. Everything was beneath us. It wasn’t helping that Kristen kept looking over the edge, the steeper one to the north, that soon we’d have to ski down. There were several other narrow chutes, or “couloirs” as they’re called in Mountain-speak. And she had to look over each one to see how far down it dropped. I knew how far down it dropped. All the way to the bottom. This was the same ridge I’d once looked over the top of, years ago, and nearly required therapy to recover.

Eventually we made it across the ridge to the tiny platform of snow atop North Pole Plunge. I really, really didn’t want to look down, since I was already a basket case. And the several others who were here seemed curiously reluctant to proceed as well. They were just sort of hanging out: a young couple, with snowboards; a thirty-something yuppie-looking, marathon-runner type; and a grizzled older fellow, with gray hair and zero body fat. He’d probably done this several times already today.

Finally the snowboarders set off, and tight-turned their way past some rocks and down the chute, which was narrowest right here at the top. About the width of two skis, end to end. It was so steep the snowboarders dropped immediately out of sight. Great.

I wanted to get this over with because on present trajectories I was going to soon be paralyzed with fear. I wasn’t handling it well at all.

“Kristen, let’s get our skis on,” I suggested. I knew everything would be less stressful once my skis were on, and so it proved. Half the fear evaporated once on skis. Why? Because on skis I wouldn’t lose my footing and slide to the bottom through this rock field. That could only happen if I fell, and I wasn’t going to. It was too dangerous. Falling wasn’t an option.

The grizzled, grandfather-type started to move forward, and I immediately deferred to him. Anything to postpone.

“Go ahead,” I said, politely. “We’ll follow you.”

And this is where I got paid the highest compliment of the day, the ego-boost that somehow filled me with confidence and resolution, the psychic energy needed to complete the quest.

“No, I’d rather you go first,” the kindly man said. “I don’t quite know how to get past these rocks at the beginning, and I need to see how you do it.”

Hmm. Yes. There were rock outcroppings and icy patches and all manner of hurdles right here at the top. But it looked like if I could get through them, everything widened out and the snow got deeper below. OK, so now I was the mountain guide. It gave me assurance, there being someone here perhaps even less secure than me. Of course, maybe he’d been stationed up here by the ski patrol, to say the same thing to everyone, and thus help them overcome their anxiety. Yeah, the old “I need to see how you do it,” line.

If that’s what it was, it worked. I had my skis on now and all I had to do was get through this nasty, narrow rock field. On foot it would have required ropes, crampons, and ice axes. But a ski is six feet of sharp, steel, edge. One on each side of the ski. And you have two skis. From a physics standpoint, this is a vast amount of control—far surpassing a mere force like gravity.

A squirrel might be nervous, at the top of this chute, but a bird wouldn’t be, because a bird has wings. A hiker might be frightened here, but a skier shouldn’t be. A skier has skis.

I slid down to the rocks, sort of hopped over them sideways, executed a couple of quick turns past the remainder, and I was through. I did not look back up. Nope. Great way to lose your balance. I kept looking down. And now I could see where I was going.

Steep? Yes. But we were below most of the rocks, and the snow was good. A-Basin had received almost a foot of new snow since Wednesday. Every turn I made brought me that much closer to being out of this nightmare. As the chute widened dramatically, I saw Kristen skiing beside me, taking it very carefully, not worrying too much about form, and focused instead on simply not falling. But I thought she looked pretty good, even so. Better than me, certainly.

Skiing “steep and deep” uses tremendous amounts of leg muscles, but by this time we didn’t have any leg muscles. All energy had been consumed by the hike itself. We had no choice but to do a couple of turns, and then stop. And rest. And try to get oxygen back to the legs.

But it wasn’t like this was a race or anything. Mikaela Shiffrin wasn’t going to shoot past us, seeking another World Cup victory. Nothing wrong with slow. It had taken us an hour to climb to the top. We could take an hour to get to the bottom if we wished.

In truth it took about ten minutes. Going down is always faster. And soon the end was in sight. We were nearing the East Wall “traverse,” the horizontal line of ski tracks running sideways along the top of East Wall, itself a double-black diamond run. You follow it as long as you want, and then drop down into the bowl, at the bottom of which you meet up with the groomed runs of the regular ski area. But now we were approaching the traverse itself—from far above.

“Wow,” said Kristen. “Look at East Wall. I used to think it was steep. Now it looks flat by comparison.”

“No kidding. They should change its signage to a green run or something,” I joked, naming the color that marks the beginner slopes.

The arrogance was already setting in. We had survived North Pole Plunge. We hadn’t fallen. No St. Bernards, or rescue helicopters, had been needed after all.

Arriving at midway lodge, we hit the bar, and took our drinks out to the deck, where we could gaze up at the thing we’d just conquered, and talk about it.

The hiking had been longer and harder than expected. The crossing of the knife-edge, ridge-line, carrying ski equipment, was by far the worst part. The skiing had been challenging but not as bad as my imagination had conjured.

Yes, it was a major accomplishment. I would never have to look at North Pole Plunge from now on, and feel shame.

“Would you ever want to go again?” I asked mountain-guide Kristen.

“Nope!” she said, grinning. “No way. How about you?”

“Nope!”

But as they say is true with childbirth, the memory fades quickly and no doubt this would as well. Or perhaps a better analogy: Everyone needs to go through adolescence once. But no one wants to do it again.

The locals call it “Sh-t For Brains” for a reason. But I could feel my own brain cells already growing back. North Pole Plunge was in my past. And it could stay there.